A conversation with Gregg Alexander of New Radicals from 1998

In a long interview conducted during his fleeting moment in the limelight, the alt-pop enigma made it clear he was pissed off about a lot more than Beck and Hanson, Courtney Love and Marilyn Manson

Welcome to stübermania, where I dig into my box of dust-covered interview cassettes from the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s to present bygone conversations with your favourite alterna/indie semi-stars. This is a newsletter in three parts: The Openers (links to recent writings, playlist updates, and/or other musical musings), The Headliner (your featured interview of the week), and Encores (random yet related links).

This is a free newsletter, but if you really like what you see, please consider a donation via paid subscription, or visit my PWYC tip jar!

THE OPENERS

Spotted this week: the most mystical minivan in all of Southern Ontario.

A heads-up: This will be the last regular edition of stübermania for 2024. For the final two Thursdays of December, I will forsake the usual featured-interview format to bombard your inbox with year-in-review retrospectives, because the law dictates I must do so in order to renew my music-critic licence for another year (I don’t make the rules). Thank you for coming along for the ride up to this point, and if you’re newish to the newsletter, you can get caught up by taking a deep dive into my archive of interviews with the likes of Jarvis Cocker, Kim Deal, Paul Westerberg, Courtney Love, and many more.

This will also be the last update to the stübermania 2024 playlist, before I start building the 2025 edition. Here’s your final delivery of newish quality choons:

The Cure, “I Can Never Say Goodbye”: I’m not sure why it took me weeks to get around to listening to the new Cure album—maybe I just needed snow on the ground and an outdoor temperature cold enough to make my breath visible. I’m finding myself most drawn to this frost-covered power ballad, where Robert Smith eulogizes his late brother and uncorks the waterworks through a guitar solo that’s as beautifully messy as his eyeliner.

Straw Man Army, “Extinction Burst”: I got turned onto this New York power duo through Evan Minsker’s garage/punk newsletter see/saw, and the hectoring artcore of their recently released album Earthworks is filling the Minutemen/Mission of Burma-sized hole in my soul. (Note: Instead of just posting a best-of-2024 list like the rest of us newsletter slackers, see/saw is actually publishing a year-end print magazine that you can/should order here.)

Trupa Trupa, “Sister Ray”: As the 2:40 runtime should make instantly clear, this is definitely not a cover of the 17-minute Velvet Underground room-clearing classic—but it shares a certain perversely fun spirit. The Polish band has always injected its greyscale post-punk with dashes of kaleidoscopic pop colour, but this single from the upcoming Mourners EP (out in February) swiftly shakes off its brooding, bass-driven menace and busts into an uncharacteristically upbeat new-wave earworm destined to rule the dancefloor at your dystopian discotheque of choice.

Cici Arthur, “All So Incredible”: This is a new supergroup featuring three Toronto artists who’ve spent much of their careers pirouetting on the avant-garde/soft-rock divide: saxophonist Joseph Shabason, multi-instrumentalist Thom Gill, and singer/keyboardist Chris Cummings (a.k.a. Marker Starling). This daydreamy delight from their debut album, Way Through (out Feb. 21), hovers in the liminal space between lonesome piano-bar serenade and ambient new-age soundscape, with Owen Pallett’s string arrangements and Dorothea Paas’ heavenly harmonies bringing a sense of motion to its inherent stillness, like a gust of wind pushing a cloud across the sky.

Basia Bulat, “My Angel”: The Montreal indie-pop perennial has undergone many evolutions over the past two decades, from the autoharp-plucking folkie of 2007’s Oh, My Darling to the girl-group-soul revivalist of 2016’s Good Advice to the string-quartet conductor of 2022’s The Garden. This single from the upcoming Basia’s Palace (out. Feb. 21) promises another exciting transformation—into disco-dancing queen.

Click here for the Apple Music version of the playlist.

THE HEADLINER:

A conversation with Gregg Alexander

The date: December 1, 1998

Location: The Friar & Firkin, Toronto

Publication: What! A Magazine

Album being promoted: Maybe You’ve Been Brainwashed Too

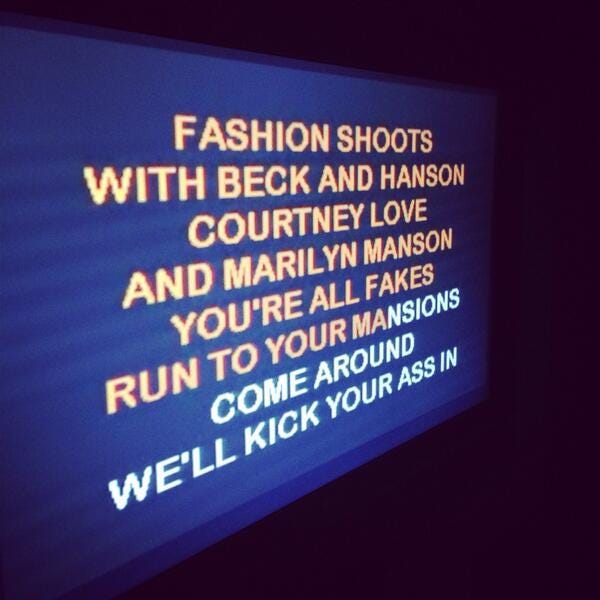

The context: There are few sure things in life, but I am certain of this: If I find myself in any sort of karaoke situation—whether at an open-mic night, in a private party room, or with live-band accompaniment—I ain’t leaving without jumping on this jam.

However, as the following interview makes abundantly clear, the idea of New Radicals’ “You Only Get What You Give” becoming a feel-good karaoke staple would’ve mortified the song’s writer, Gregg Alexander, back in 1998. Because for him, a pop song was more than just a delivery mechanism for pleasure—it was a Trojan horse that he could use to smuggle revolutionary rhetoric and critical thinking into mass consciousness. At the time, Alexander’s group may have been jostling for space on the Billboard modern-rock charts with the likes of Sugar Ray, Fastball, and The Goo Goo Dolls, but the singer was giving interviews that read more like Godspeed You! Black Emperor manifestos, sounding off on corporate America, media complicity, youth apathy, and irony-overloaded alternaculture.

We’re used to hearing about suddenly successful musicians who develop a deeply uncomfortable relationship with the spotlight, but Alexander wasn’t just being dramatic. Let’s just say that, after doing this interview, the news of New Radicals’ demise a few months later did not come as much of a surprise to me. Even though we were speaking just a few weeks after the release of New Radicals’ debut album, Maybe You’ve Been Brainwashed Too, Alexander spoke like somebody who was already drafting his exit plan. In hindsight, his disappearing act was the canary in a coalmine for a modern pop era where artists have become evermore vocal about the parasocial pitfalls of celebrity and are willing to walk away from lucrative tours to preserve their sanity.

I did this interview for Canadian teen periodical What! A Magazine the day after New Radicals’ first and only Toronto show to date at Lee’s Palace. We met at the Friar & Firkin pub across the street from the MuchMusic building, where Alexander had just done this live interview with Sook-Yin Lee:

My original piece for What! was a 500-word quasi-sidebar feature that used maybe five percent of our conversation. Longer excerpts of this interview would later appear in my 20th-anniversary New Radicals retrospective for Stereogum, and I’ll let the introductory paragraphs from that piece set the scene for the complete transcript below:

For an emerging artist, a hit single is both the best and worst thing that can happen to you.

On the one hand, having your song all over radio and MTV essentially guarantees your first-ever national club tour will be sold out. On the other hand, it turns every show into an awkward waiting game, where the audience politely endures every song on the setlist that isn’t The Hit, until The Hit is played and everyone loses their shit for three minutes, and three minutes only. If you drop The Hit too early in the set, everything from that point on feels anti-climactic. But if you save it for last, the big moment feels too premeditated — it’s like walking into a surprise birthday party for yourself that you already knew about.

I don’t remember too much about the time I saw New Radicals play their one and only Toronto gig at Lee’s Palace on November 30, 1998. But I do remember them dropping The Hit in the middle of their set and thinking it was a ballsy move. As it turns out, it wasn’t that risky a proposition, because New Radicals had a failsafe plan for going out on a high note. For their encore, they did something I had never seen a band do before and haven’t since.

They came back onstage, and played The Hit again.

So at your show last night, you played “You Get What You Give” twice. Most bands in your position—with a huge hit all over radio—tend to start resenting their big popular song. Were you making any sort of statement by playing it twice—like, “I know this is what you really want to hear, so here you go!”

No, I would say if I were to completely separate myself from any ingrained cynicism, which is so prevalent today, and I were just to jump into the context of being onstage in front of a crowd of people that I don’t personally know, but had actually made the effort to come out and see a band that maybe they had heard one song on the radio by, or somebody said, “oh will you please come down and hear this band,” or whatever the context is, because there’s a million contexts… that was a chance to just maybe go into a little celebratory mode in a live context, which is different from the spirit of the album. With the album, there’s a spirit of euphoria in the music, but lyrically, there’s a lot of social commentary in there, and I don’t want the shows to be heavy-handed. When we go out there, we’re not afraid to be vulnerable and happy, even if it’s only happy for the moment. It’s not as if any of us in this day and age are living charmed lives. Everybody has job insecurity, everybody has career insecurity, everybody has relationship insecurity. We’re in an era where everything is systematically designed to make life as emotionally and physically hand-to-mouth—we’re always hand-to-mouth, even our emotions.

And that’s how corporations make money—by feeding off people’s insecurities.

Absolutely. That’s one of the heartbreaking things about society right now. That’s actually why the album’s been called Maybe You’ve Been Brainwashed Too.

I noticed every press photo of you has a barcode on it. Are you starting to feel like a product?

No… on some level, but I would say because the actual currency is music, and something from the heart, it’s a chance to communicate an emotion to people. If it was anything but music, I might feel a little different about it, and after everything I’ve learned the past couple of years, it wouldn’t be satisfying putting out music if it wasn’t going to be leading up to something—knock on wood—that’s going to share a point of view with people. And when I say point of view, I don’t mean my point of view, I mean the point of view of a lot of people in society who are frustrated and freaked out at the fact that they can’t get health insurance at a young age. A couple of things I talk about a lot, because I feel very passionate about them, is the fact that kids are encouraged to get into $10,000 of credit card debt by the time they’re 19 years old, and they’re paying 20 per cent interest. It’s vulgar behaviour, and we’ve become so Americanized all over the world that it seems like every culture and new generation accepts the cards we’re dealt and our circumstances. We just embrace it. I’d like to think we can use rock ‘n’ roll and pop culture to maybe fight against that a little bit.

Do you think that’s possible? I find the record has this really jarring contrast between cynicism and unabashed optimism. Are you yourself torn between saying, “ah, fuck this” but also doing something about it?

Absolutely. I would say that “cynicism” might be replaced by the word “realism,” though. There’s a part of me that’s really optimistic, and really believes in the magic of love and the ability of the human spirit and human beings to really care about each other, and do the right things and stand up for each other, and pull through. But on the other hand, I’m also a realist about what society has mutated into since the technological age.

So you’ve got a hippie heart, but a punk brain?

[Laughs] That would be a good song title! I don’t know if “hippie” is the right word, because the problem with the word “hippie”—and I know it’s not your term—is that it was an excuse for the mainstream media… I would say that was one of the major shortcomings of society in the 1960s. The western world blew it, because we had a chance to really embrace a mass rebellion philosophically against consumer culture, greed, and no accountability behind all the dishonesty and corporate thievery and horrible things that created our modern world.

And what the media did back then, and which mainstream America stupidly embraced wholeheartedly, was the whole notion and cliché of hippies as being these long-haired freaks, and the fact that even punks were stupid enough to buy into the cliché of “aw, we’re punks and we hate those hippies”—hippies and punks aren’t that different! They were basically at the core, saying, “Hey everybody, pay attention to what’s going on.” Punks were doing it by saying, “pay attention to me, with my nose ring” and the bells and whistles of what a punker was on some level, and maybe goths too…. Really, you either care about and want humanity to pull it off and come through on the other side with something to show for besides a destroyed environment and a stockpile of nuclear weapons that are inevitably going to be used in the next 30 years if we don’t change things drastically, or you believe in the status quo.

It’s tough. I’m 23, just out of school, and a lot of people I know are trying to get hired by corporations, and they just want it to be a temporary thing, because they just want to save up to travel or whatever. But before you know it, you’re almost 30 and you’re making 70 grand a year, and it’s hard to let go of that. At the same, there’s this shift toward contract work, where you’re not considered a full-time employee, so you don’t get any benefits, but you have to devote your entire life to the job.

Yeah, 85-hour weeks. And the scary thing is, it’s no different from the record business or in the media side. We all need to fight against it, and we all need to talk about it and scream about it, because ultimately what we’re all left with is zero security. You dedicate 80 hours a week of the best years of our life, all to do what? Maybe to get into a position where, if we are really political and we really maneuver the way society is systematically set up, the best we can come out with for most people is some job making a lot of money where we’ll probably get fired after two or three years anyway, because office politics these days are so catty and cutthroat that people end up sabotaging their competition anyway. That’s the thing that’s so unbelievable: The culture of corporate dog-fighting is present even in lower-echelon jobs. It used to be CEOs all trying to outdo each other’s companies, and now there’s people making $40,000 a year trying to smear or talk about or discredit their competition.

You already had one sour major label experience as a solo artist, and judging by your lyrics, you seem to despise everything major labels—and their corporate parents—stand for. So why go back to a major label with New Radicals?

I would say there’s no differentiation unfortunately between indie labels and mainstream labels now. The most interesting exercise for me of the full fruition of the alternative-music movement of the early-‘90s was that we all got to see first-hand that all of those indie-rock bands and alternative-rock bands and indie labels, at the end of the day, were no different than the mentality of the people who were on TV shows like Dynasty. They all sold out, they all went for the money and all the indie labels are practically owned by major labels now. So, if you’re writing songs such as myself and you have a point of view on the world, and you’re around people who have a really strong point of view on the world—because I have friends who are all freaking out about the things that we’re talking about—it’s not like I’m on some mission or I’m some rallyer of justice. I’m not self-delusional.

But there is a strong percentage of people that feel passionate about these things, and the only way for me as a singer and songwriter and pop-propaganda person and a renaissance man—because I have a lot of different hats that I wear—I would say the most relevant way to get that across is through the power of rock ‘n’ roll and the uplifting euphoric power of song and dance and being able to release your spirit. The nuts and bolts of it, unfortunately, is that if you sign a record deal with an indie label, it’s the exact same thing as a major label—the only difference is a major label gives you a better chance to get your music heard.

My agenda, and my purpose for why I’m doing my music is way bigger than proving my credibility to indie-rock kids who have parents supporting them anyway. Because usually the people who go around saying “so and so sold out, or punk bands who have their 18-year-old fans say “you sold out”… I’ve been to pubs sometimes where there’s young people in suits and they’re all making money and there’ll be a rock video on TV and they’ll say, “oh, those sellouts…” Who the fuck are you to call them sellouts? Those guys [on TV] will probably be living in the street anyway. Because that’s the thing about most rock bands: The turnover is so quick.

Do you find it’s hard to be sincere when everything today is so tongue-in-cheek or ironic?

Oh fuck yeah. That’s one of the other things I’ve got my boxing gloves on about—I’m ready to go out there and fuck shit up. Because as far as I’m concerned, that whole mentality and that whole Silverlake chic thing of “oh, aren’t we cool” and lyrics like “the beercan fell into the washing sink of dreams and it came up with a purple smile on its face”—it’s like, fuck that shit! Quit living in your white-bred world. Tune into what’s going on in the real world. Don’t bore us with that shit. Those things actually do get under my skin. Because it’s rock ‘n’ roll recreating the same vague, apolitical bullshit as a fucking Coca-Cola commercial. There are particular artists I could go on about, but I won’t get into it, because I know there’s that interpretation of that lyric, but… absolutely: It’s like all he is is a fucking alternative soda commercial. What do these people have to say about the fucking real world? All they talk about is their hip friends and their movie premieres and all this stuff—it’s like, who gives a fuck?

I’m sure that lyric has been thrown back at you a million times—but is there not a part of you that would like to be on the cover of SPIN and use that platform?

Oh that’s a piece of cake, that’s a cakewalk. I’ve got the tools to fulfill all the superficial shit. But I don’t want to do that. I would say that anybody that wants to make their self-aggrandizement the big picture, it’s a cake walk. That’s what celebrity is these days: playing by the rules and getting your rewards. Fuck that.

Now that your single is being played by modern-rock radio, are you afraid of people thinking you’re just the next Matchbox 20?

I’m following my gut instinct and talking about the things that mean a lot to me, and when I was in the studio making the record, and recording those songs that were really personal experiences, and the process of making something as abstract and ridiculous as a pop video, I’ve tried to make it fit in with where my head is at. So if I get misinterpreted or turned into something I’m not by the machinery, that huge fucking money-making media machinery across the board, I can’t control that. I won’t sit around and cry about it. What I’m going to know is that I’ve done my best with the people who I think need to pick up the ball: writers, people who are hosts of TV shows, other musicians that get a chance to hear Maybe You’ve Been Brainwashed Too… it’s about all of us as human beings and artists picking up the ball and talking about these personal issues for people, it’s not about it being an ego thing.

I don’t have any desire to have ownership of any particular human rights movement, I just want to see people be consciously aware of what’s going on around us—if it’s not stopped, it could signal the end of mankind. There could be a nuclear catastrophe tonight. We have a country like Russia breaking down economically, and there’s a stockpile of nuclear weapons—it doesn’t take much common sense to realize that, at some point, when people’s children are starving to death, why not pawn off 30 nuclear weapons to a rogue nation, because we need to feed our children tonight. Those aren’t really subversive comments. That’s the thing that sucks about pop culture: When I talk about this stuff, sometimes I feel like I’m treading on dangerous ground. And that’s the thing that’s so fucked up about our society: We could talk about what a babe Pamela Anderson is, but we can’t talk about real issues. So what it signals is that the media and the rock ‘n’ roll machine and rock stars and film stars have all hand-in-hand walked into our own oppression. We’ve all gotten little tablespoons out and started adding to the grave. We’re digging the grave too—maybe we don’t have a big ditch or bulldozer, but we’re adding to it.

Do you buy into pre-millennial theories about computers getting wiped out in the year 2000?

Let’s see what happens. All the signals are definitely implying that the situation is not under control. Did you see that story in the paper about how, in a lot of these different countries, the nuclear weapons systems that they said were okay for the year 2000 bug are not ready. These things are in the newspaper, but the thing that’s so weird about society nowadays is nobody fucking talks about it.

Well, it’s like every ad campaign these days is based on a catchphrase like, “Whatever…”

That’s the thing I thought was such a letdown about the whole ‘90s rock ‘n’ roll thing. It was all about that whole “whatever” thing…. rock ‘n’ roll is supposed to be a voice against oppression, not an apathetic grunt.

You obviously have a lot on your mind, and your lyric sheet is almost as dense as the Unabomber’s manifesto—do you feel constrained by the limits of the pop songs?

I’ve got a lot of places to go to from here. For me, when I’m writing a song, I like to hear something that’s going to alter my mood and get me out of the reality that surrounds us sometimes. I think history has proven that when pop songs or rock songs or R&B songs try to speak against oppression or injustice, it just gets turned into a wedding song three years later. You go to a wedding and you hear Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On” and people’s grandmas are dancing. I would say the tale is going to be told as to what happens over the next couple of years with what the New Radicals are about, and what the Maybe You’ve Been Brainwashed Too thing gets turned into. I’ll be curious to see.

Are New Radicals a proper band now?

Yeah, but it’s still an open door. The concept and notion of what philosophically the album and the band is supposed to represent is not supposed to be represented by any particular person, it’s really more about the music and the point of view behind it. I could be anybody.

This record seems to have a lot of cross-generational appeal—I know some older people who’ve said it reminds them of Todd Rundrgen, but I’ve also seen comparisons to everyone from Prince to World Party to Ben Folds Five. When the day is done, who would you want your record sitting next to on a record shelf?

I don’t really think about that. I don’t have any particular desire to be aligned with anything from the past or the future. Maybe the reason why my music is hard to categorize is I write the songs on acoustic guitar in like four to six minutes—it’s almost like channeling. Sonically, sometimes, there’s a frame of reference—like a snare sound I heard on a record I liked when I was 17. But other than that part of it, when I write songs, it’s a reflection of my spirit.

Do you see yourself in Detroit tradition?

I would say energy-wise and spirit-wise, maybe… I see myself as a world citizen. That’s the thing I think is so bizarre, but it makes sense to me how a lot of people live in a bubble. When you live in a bubble, it’s easy to become specific to a certain community, like, “I am a Detroit singer/songwriter.” I always thought I was thrown to the wolves. My parents weren’t exactly the most functioning family unit. I wasn’t exactly running outside in my underwear in the snow at four years old or anything like that, but I was definitely left to my own devices.

I kind of see myself, and I think all of us should if we were really to take a close look at who we are and how we’re living, and the times we’re living in, we’d realize we’re more citizens of this insane time in the history of mankind… When TVs and the media and the information society have gone really out of control, we’re the children of that era, much more than we’re the children of Toronto or Detroit or Chicago. Even rivalries between towns, like, how the people from the south high school don’t like the people from the east high school, it’s like, why? Don’t separate yourself from city to city, whether you’re black or white or fat or skinny or a girl or a boy. Let’s unite ourselves.

It’s interesting: your record-company bio paints you as this try-everything-once hedonist, but I get a sense from the record that sort of lifestyle has left you with a spiritual void.

The truth—and this is one of things that’s difficult about me doing press for this record—is: I am out of fucking control, I’m definitely not the boy next door. But to discuss that stuff is really probably one of the most pretentious wanker things you can do. It’s just been a part of the whole experience of talking about something that is passionate to me. I would say that’s a reflection of what my life has been so far: I’ve had some ridiculous experiences. But I think spirituality is imperative… and this is a dangerous topic to talk about without sounding like a wanker, it’s a real conversation that needs to happen for hours.

Most of the things we’ve been talking about are difficult in the context of someone knowing one song… I’ve found with the little bit of press I’ve done, when you talk about something, it gets filtered, so why even bother going on these diatribes, if it’s not being used to hold a mirror up to society? That’s the thing about kids out there: They’re subconsciously aware of the perversion of what society has turned into. It’s comforting for them to have it reconfirmed by the magazines they read or the movies they watch, so they don’t feel like they’re losing their fucking minds. That’s why there are so many kids killing themselves, there’s so much depression, so many runaways, so much dysfunctional stuff going on in families and stuff like that.

ENCORES

Long after his moment in the Buzz Bin, Gregg Alexander remains a fascinating figure to me, because he’s managed to strike the perfect balance between ubiquity and anonymity. New Radicals may be long gone, but Alexander has had an invisible hand in several hit singles over the past quarter century, including the 2003 Michelle Branch/Santana collab “Game of Love,” which is basically “You Only Get What You Give” subjected to a “Smooth” makeover…

…and then in 2014, he co-wrote the Oscar-nominated song “Lost Stars,” featured in the Keira Knightley/Mark Ruffalo rom-com Begin Again and later covered by Adam Levine…

…while 2024 has been Alexander’s most publicly active year since the New Radicals’ heyday, thanks to the Saltburn-assisted revival of his 2001 Sophie Ellis-Bextor co-write, “Murder on the Dancefloor”…

…and his recent release of New Radicals’ version of the song, which Alexander began writing in 1994 and originally envisioned as New Radicals debut single.

And while New Radicals didn’t mount a return to the stage, Alexander could be seen stumping for Kamala Harris with his new BFF Doug Emhoff. Alexander may no longer be the outspoken provocateur he was in 1998, but he’s clearly updated his shitlist to include fascist goons like Trump and Vance and Elon Musk and Stephen Bannon.

This is a free newsletter, but if you really like what you see, please consider a donation via paid subscription, or visit my PWYC tip jar!