A conversation with Jarvis Cocker from 1998

The Pulp frontman on life after Britpop, making adult-contemporary pop music that isn't shit, not understanding 22-year-olds, and why he's mortified by his early records

Welcome to stübermania, where I dig into my box of dust-covered interview cassettes from the ‘90s and ‘00s and present bygone conversations with your favourite alterna/indie semi-stars. This is a newsletter in three parts: The Openers (links to recent writings, playlist updates, and/or other musical musings), The Headliner (your featured interview of the week), and Encores (random yet related links).

This is a free newsletter, but if you really like what you see, please pay a visit to my PWYC tip jar!

THE OPENERS

Notes on this week’s additions to the stübermania 2024 playlist:

Jade Hairpins, “Get Me the Good Stuff”: It’s been a busy summer for Fucked Up’s Jonah Falco and Mike Haliechuk—not only did their main band drop two new albums last month (including one recorded in a single day), they’ve also gone back to their side hustle, the more melodious and omnivorous Jade Hairpins. The group releases its second full-length, Get Me the Good Stuff, this Friday on Merge, and on the radiant title track, they perfect a power-pop/electro-funk hybrid best described as “disco Sloan.”

Jennifer Castle, “Lucky #8”: After nearly two decades in the Southern Ontario indie trenches, this Bear-approved songwriter is seemingly approaching the sort of breakthrough moment that her peers U.S. Girls and The Weather Station respectively experienced with In a Poem Unlimited and Ignorance. The irrepressible, string-swept jangle of “Lucky #8” is an exemplar of the gold sounds that await you when Castle releases Camelot on Nov. 1.

Chimers, “3am”: As if we needed more evidence that Australia is producing all the best rock bands these days, this power duo imagines what the first Foo Fighters album might’ve sounded like if it had come out on Creation Records.

Nemahsis, “coloured concrete”: The new album from this Palestinian-Canadian singer, Verbathim, was written and recorded before the war in Gaza erupted last October, but its release was delayed after she was reportedly dropped by her label for her social-media posts on the conflict. So if the record doesn’t fully reflect where her head is at now, this track is at least perfectly timed to catch the post-Chappell wave of ecstatic alt-pop bops.

MJ Lenderman, “On My Knees”: There’s good timing, and then there’s “MJ Lenderman releases a song that starts out just like ‘Supersonic’ the week after Oasis reunites” good timing.

Cuff the Duke, “Got You on the Run”: If the Lenderman record has you hankering for more alt-country in your pantry, you should know that early-2000s survivors Cuff the Duke have just released their first new album in 12 years, Breaking Dawn, which upgrades their Tom Petty-via-Blue Rodeo roots-rock with some Summerteeth sheen.

LL Cool J, “Basquiat Energy”: I don’t think anyone had “LL hooks up with Q-Tip to make the best ‘90s-rap record of 2024” on their bingo card, but here we are.

Click here for the Apple Music version.

Now here’s a sentence I haven’t been able to type in 26 years: I saw Pulp perform last night. Here are five quick thoughts on the evening:

Ian Svenonius is opening the Pulp tour (as Escape-ism), a fact that seems severely underreported.

Pulp have so many A-plus choons in their repertoire, they can afford to drop this one two songs into the show:

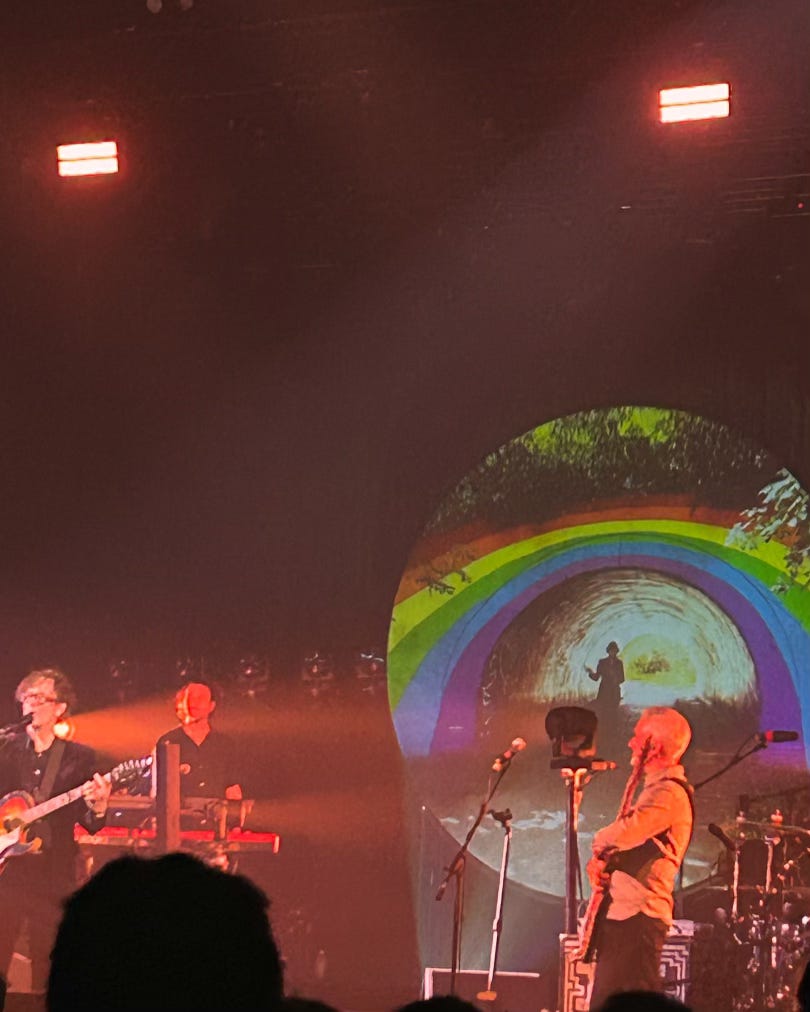

During his visit to Toronto, Jarvis took a walk through the rainbow tunnel near the DVP—and now Pulp have a new onstage backdrop:

There are some days where I think “Common People” is the greatest song of all time, and that is most days, but especially on this night, at this precise moment:

And “Razzamatazz” is a close second:

Speaking of Pulp…

THE HEADLINER:

A conversation with Jarvis Cocker

The date: March 13, 1998

Location: Cambridge Suites Hotel, Toronto

Publication: Chart

Album being promoted: This Is Hardcore

The context: When faced with the choice of Blur or Oasis, the correct response is always Pulp. Among their fellow NME pin-ups, the Sheffield band always struck the most harmonious balance of arty and anthemic, glamour and squalor, comedy and critique. But by the time they released This Is Hardcore, they were feeling like a very different band than the one that stormed the castle with 1995’s unstoppable Different Class. I’ll let this blurb I wrote for Pitchfork’s Best Albums of 1998 feature set the scene:

Several events can be pinpointed as the moment Britpop died: the release of Blur’s discordant 1997 self-titled album; the debut of the Spice Girls; that feeling that sunk in when you hit minute three of Oasis’ “All Around the World” and realized, “Fuck me, there’s still six minutes of this to go.” But there’s no disputing that This Is Hardcore was the tombstone dropped onto the grave: the heavy, dark-grey monolith that brought resounding finality to it all. Pulp were the outsiders who saw themselves as bystanders to the Britpop party, but still managed to get sucked up in the cocaine supernova; This Is Hardcore was Jarvis Cocker’s distress signal sent from behind the velvet rope at 4 a.m., when the club lights flip on and expose all the cigarette smoke and desperation hanging in the room.

But if the overall mood of This Is Hardcore was doomy and depraved, in this interview for Chart magazine, Jarvis was most chatty and cheerful. Technically, this was a conversation with Jarvis and guitarist Mark Webber, but the former did 99.8 per cent of the talking.

I was reading the press that came out around the time of Different Class and the central theme among most of the articles is that Pulp are here to save the working classes and stand up for the outcasts in society. But I find on this record, there seems to be a more humbled perspective, with songs like "Dishes" and "The Fear." Was that whole “spokesperson for a generation” responsbility a little too much to handle?

Jarvis Cocker: Well, I just think if you try to keep up that kind of thing, you end up making some quite crass statements, you know? The time at which that record was made, Different Class, it seemed like there was an upheaval, like an invasion of the mainstream, if you like. And it seemed like, "yeah, now is the time that these people who've been shat on for a long time can now not be considered, like, marginal losers wearing anoraks, but actually be kind of included." But you know, having seen now what has actually happened, that dream couldn't survive. I still believe in the working classes as being the most interesting people, and the most energetic people, where all the kind of impetus and creative stuff comes from in our country, But I think they're better off just keeping it for themselves and fuck the middle class for not providing entertainment.

You get that sense on "The Day After the Revolution." It's like anti-climax—you've won, and then it's like, "now what?

Jarvis Cocker: I wondered what would happen, you know, on the day after a revolution. An old order has been destroyed, but immediately, I reckon, human beings, being what they are, would kind of look around desperately and look for someone to follow. And gradually those kinds of institutions and structures get built up again. I think the way any kind of culture works is like a pendulum. It swings from one way, and then it swings back because you get to a certain thing. Like, one of the movements within our culture has been this kind of new laddism—Loaded magazine and all that kind of stuff, you know. I suppose it was a novelty that suddenly men were allowed to look at pictures of barely clad women and stuff like that, and kind of admit to farting in the bath or something like that. I guess it was funny for a couple of seconds, and then it just started manifesting itself in quite narrow-minded, macho kind of attitudes. I think there's a reaction against that now, because it's just turned into something really horrible. It’s really quite nasty towards women a lot of the time.

Well, at the time of a Different Class, I noticed in a lot of interviews, you’d paraphrase Patti Smith and say “inside society is where I want to be.” Has success changed your outlook in that regard?

Jarvis Cocker: I have changed my opinion on that, yeah, because I just think it’s castrating. The way that mainstream works is to kind of smooth everything over and bland everything out. I was going to concerts, and just getting sick of getting me feet trodden on, and listening to a concert with really shit sound, it’s all echoing around a big place, and all these daft kids getting on your nerves. And then going to another place maybe where there's maybe 300 people, and you can actually have a conversation about something reasonable, and you haven't got that thing of getting your feet trodden on the whole time, and I thought, “I'd rather have that.” It just went too far. Because it seemed really important, living in the UK in the 80s, as we did, and it was very much the Thatcher generation, of people kind of shoved off to one side, on the dole, basically told, “you haven't got any place in this society.” And so it seemed very important to get a voice. So I don't regret all that, but you kind of realize why underground and alternative music first came into being, because of this kind of horrible corporate shittiness.

You’ve earned the reputation of being a master storyteller and keen observer of social mores. But now that you’ve achieved a level of success, can you access the working class in the same way? Can you sit in the coffee shop and just enjoy yourself without getting hassled?

Jarvis Cocker: It's not that difficult, you just have to be more imaginative. You know, I wouldn't go into a pub in the middle of London on a Saturday night.

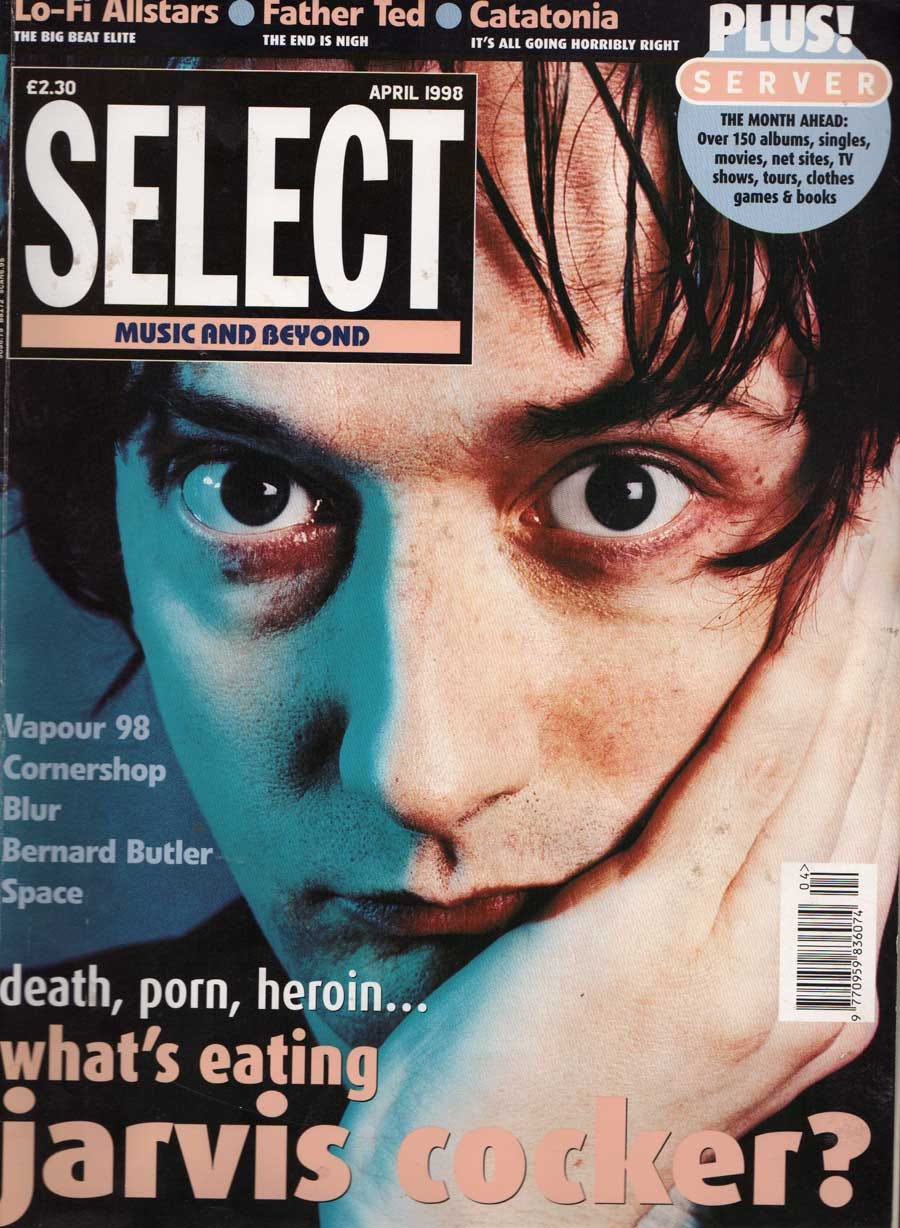

So we just got the Select magazine with your cover story…

Jarvis Cocker: Oh yes, about my heroin problem… [laughs]

So what’s worse: being branded the spokesperson for a generation. or a death-obsessed porn addict?

Jarvis Cocker: I don't know, really. It did me in, that article. It’s supposed to be a music magazine, and it's, like, tabloidism. There's not much you can do about it. If you kind of stamp your foot and complain about it, then everybody assumes it's true.

It’s funny that they sort of focused on the porn aspect of the word “hardcore,” because the first time I heard the title, my first thought was hardcore punk rock…

Jarvis Cocker: So you were a bit disappointed, then…

Well, usually when you think of hardcore punk, it’s guys with shaved heads screaming. It's not very sexy or glamorous, which is sort of the exact opposite of Pulp’s music. So I was wondering if there was any irony on your part in using that word…

Jarvis Cocker: The word “hardcore,” if it's applied to music, tends to be associated more with, like, hardcore house kind of stuff, which is really the most brutal house that's really quite Neanderthal. I suppose it's operating in the same area as hardcore punk. There's an element of that, yeah. It's a bit more of a hardcore record. It's made for hardcore people.

Well, speaking of porn… have you seen the Pamela Anderson/Tommy Lee video?

Jarvis Cocker: No. I had an opportunity to see it. A friend of mine in New York had a copy. He said it was touching, because he realized that, although Tommy Lee is obviously quite dumb, he really seems to be completely in love with her.

The advance word on the new album was that it was less accessible and darker. Did Island Records have any problems with it? Because there was word that, after the last U2 album didn't exactly blow everyone away, they were really hoping for a big hit from you guys…

Jarvis Cocker: We're not really there to bail the record company out of their shit. We're there to do something that we can live with. We didn't make a record that was darker on purpose. We don't want to try and bankrupt them. But it's not our job to sort the record company’s balance sheet. Island have been very good to us—they never come down to the studio. Some record companies do that — they come down and insist on listening to stuff and interfere. Island don't do any of that. They just let you get on with it.

Pulp has always been very theatrical and glamorous, and This Is Hardcore is a very grandiose album. But how do you avoid turning it into a spectacle and venturing into Michael Jackson territory? Do you have a bullshit detector?

Jarvis Cocker: Well, some aspects of Michael Jackson territory are alright. But we're not going to be having the statues floating down the river In the end. The more successful you get, the more you have to rely on your bullshit detector, as you put it, because you can't really rely on other people's opinions that much, because they'll probably just tell you what they think you want to hear.

I find “Help the Aged” to be a very endearing track, because rock ‘n’ roll has long been considered the music of youth. Are you trying to close the generation gap?

Jarvis Cocker: I don't know about that. It's just thinking about yourself as being an oldish performer in a youth-oriented market. I'm only about six months younger than George Michael, and he really wants to go into the AOR/Elton John market, and that's where he wants to go. I would like to think that there's room for a different type of AOR, i.e., not shit and not completely boring and bland. Because if all AOR music is really safe and has lots of saxophone solos on it, that implies that adults are kind of neutral, bland people. And the last thing I want to do is turn into a neutral band person.

Do you find you identify more with youth than people your own age?

Jarvis Cocker: I've become aware of a generation gap in the last few months. If I speak to people who are, like, 22-23, I'm aware of the fact that I'm a lot older. And I think, “you stupid shits!”

Have you encountered any blatant instances of ageism towards you?

Jarvis Cocker: No, but I'm sure they're on the way now.

Over here, there's a growing resentment toward the older generation, because they're the reason we're going into debt and our generation has to pay for their indulgences. And we're going to be broke because there's not going to be any pension funds left once they're through with it.

Jarvis Cocker: Oh, yeah. There's an aging population, it's going to be a global problem, because there’s going to be less people working and paying taxes and lots of people wanting to claim the pension. I say, send them to the moon. Because they found water there now! They would be able to get around easier, because there's less strong gravitational pull. They might even look a bit younger, because the gravity can’t be pulling their flesh down. I'd go there. I’d rather be there than on Earth being reminded about how decrepit and shit I was.

So Different Class came at a time when Britpop was the catchphrase on everyone's mind. But do you feel any affinity with current British pop groups? Because most of them are so lyrically vague, which is the opposite of your songwriting.

Jarvis Cocker: That's true. Obviously that was a big factor in the last record’s success: it came out at a time when it was kind of appropriate and seemed to kind of fit in with what was going on in a strange way, which was weird for us, because we never have fitted it. Obviously, the British music scene has changed quite a lot in the interim, so I really don't know whether this one is going to dovetail neatly into the social fabric or otherwise.

Have you ever considered writing a novel or something longer form?

Jarvis Cocker: I've considered it yet. I've never even vaguely attempted it.

Do you feel compromised having to stick within the format of a pop song?

Jarvis Cocker: I think pop songs are really undervalued. I like the words to rhyme. That, in itself, is something that gives me a lot of pleasure. Because poetry shouldn't rhyme if it's serious poetry, but songs should, I think. I really like it. It’s an art in itself. A great song can be as great a work of art as a painting that might have taken six months, or even a novel or something. And yes, songs only last, like, four or five minutes. I like the fact that it’s really concentrated. You wouldn't keep reading a book every week. Whereas a song, if it's your favorite song, you might play it, like, four times a day. Sometimes repetition actually makes it better. There's not many other things where you keep experiencing it, and you might actually end up getting more out of it. I mean, I know kind of people kind of do it with films a bit now – you might watch a favorite film a few times. But you still wouldn't do it as much as you would a record.

In hindsight, would you say His N Hers was a major turning point for this band?

Jarvis Cocker: It was a big deal. That was the first time we did an album where we had a producer, to start. It was the first kind of coherent record, wasn’t it?

Mark Webber: It was a situation in which you could do pretty much what you wanted.

Jarvis Cocker: Yeah, it wasn't like we had unlimited studio time, but we had enough time to do it. The album before that, Separations, had been kind of done piecemeal during weekends when I was at college, or during summer holiday and stuff like that. It was pretty all over the place. And it took, like, three years to come out.

I heard that you were not very happy that the old stuff's been re-released…

Jarvis Cocker: That’s a mild way of putting it. It’s because the man who owns the rights to that stuff, Clive Solomon from Fire Records, is a fucking tosser and just the licenses stuff out, and still gets money off our records now, because of the he went to law school, so he drafted a contract that was morally wrong. And what can I say? He’s an evil man. He went with this Countdown compilation, and he tried to mimic the sleeve out of Different Class nearly as he could to dupe someone into buying it, and that's just not right.

Are those records something you'd like to forget?

Jarvis Cocker: No, you can’t forget them, unfortunately. Some of it's, like, 13 years ago. As I said, I don't understand 22 and 23 year old people, so I don't understand myself then. But if I was to listen to them—which I wouldn't—I would say, “Snap out of it. Cheer up. It's not that bad. Stop trying so hard.” I don't know if you've ever written poetry, but if you were to find some poetry that you wrote when you were 1, you'd squirm with embarrassment, wouldn't you? I can listen to those records, and it's such an accurate reflection of what I was like at that time. That's why I find them so flesh-crawlingly embarrassing, because that's how you are when you're that age.

So what exactly don't you understand about 22 and 23 year olds? What do they do that puzzles you?

Jarvis Cocker: I don't want to spoil it for them, you know? They're great. They're fantastic.

Are there any words of advice you'd give them?

Jarvis Cocker: No, that's the thing. I mean, people go on about, you know, “kids today” and “the kids are a menace” and all this. And I say, No, it's the adults of today, because the adults, for start, brought up the kids. So if the kids are a mess, it’s probably because the parents are fucked up. And the adults are more dangerous, because people kind of think they know what they're doing, and they try to give off an aura of knowing what they're about and stuff. But being one now, they don't know what the hell they’re going on about! They still have these kinds of impulses and desires within, but they kind of repress them, and so they end up becoming really strange, twisted people, and yet they're running things. They're the heads of corporations and run stores and stuff like that. And they're kind of considered to be upstanding members of society. But they’re nuts, most of them. I find that the younger people are much more sensible.

You’ve made your fondness for disco very obvious, but you've also expressed disillusionment with the club scene. How do you reconcile that?

Jarvis Cocker: Well, by disillusionment with the club scene, do you mean, like, “Sorted for E’s and Whizz?” That was the rave scene, though, and that was just a very particular movement. Clubs are great! I like dancing. I think it's great, you know, it's totally illogical, and illogical pursuits should be encouraged as much as possible.

So was disco as despised in the UK as much as it was here at the time?

Jarvis Cocker: Well, it certainly wasn't taken seriously.

But here they had mass burnings of disco records in baseball stadiums…

Mark Webber: Why did they take such an offence?

I suppose the rockers were afraid of this effeminate form of music that was threatening their supremacy.

Jarvis Cocker: It didn't get to that pitch in England, did it? I mean, there's quite a good few good records coming out of France now that are pretty discoish. There's this compilation called Respect is Burning, which isn't that good, but the first two tracks on that are really discoish. And Daft Punk are very kind of electro-disco.

It seems to be coming back.

Jarvis Cocker: Yeah I like it—that kind of really primitive disco.

So what are the plans for the near future?

Jarvis Cocker: We’re playing in Toronto in June, and then we tour North America in September, which will probably entail coming back. But if you could just give a message to your customs, because they're a nightmare! Every single time we've tried to come into this country, we’ve had to wait at least half an hour or an hour, while they decide whether you're allowed to go in. And they already know you’re coming, you've got a visa and everything, and then they just fuck you around. What's that all about? They got me yesterday—held me over the coals, for not knowing every person I was supposed to have an interview with that day.

ENCORES

As Jarvis mentioned, Pulp did return to Toronto a few months after this interview to headline a show at Massey Hall on June 10, 1998. The setlist and photos have been archived here. Fun fact: the opening act was Bran Van 3000.

This Is Hardcore is home to my favourite forgotten Pulp deep cut, “Sylvia,” which is unsurprisingly absent from the band’s current setlists, but here they are knocking it out of the (Finsbury) park in 1998:

But you know what has been appearing in Pulp’s recent setlists? Three new songs! That means we’re practically one-third of the way to a new album! Last month, they unveiled the wistful ballad “A Sunset”…

…and earlier this week in Chicago, they debuted the more upbeat, disco-inflected, and presumably Stone Roses-inspired “Spike Island” (not to be confused with the great Icarus Line song of the same name, which really deserves more than the 86 views it currently has on YouTube)…

…and at the first of their two Toronto shows this week, Pulp unveiled “My Sex,” a suave, sultry number that feels like it could’ve sashayed onto side two of This Is Hardcore.

Next week’s headliner: Kim Gordon

This is a free newsletter, but if you really like what you see, please pay a visit to my PWYC tip jar!

Fun fact: I wall rid the Toronto rainbow on my snowboard back in 2011. Video evidence: https://youtu.be/Wp7OX-QTjPc?si=uCM06DLrxEFTEd3O&t=1238

Very nice to read this the day after seeing them.