A conversation with Jarvis Cocker from 2025

The Pulp frontman talks about surviving Britpop, moving to the country, collaborating with Chilly Gonzales, the death of music media, and urban-exploration expeditions along the Don Valley Parkway

Welcome to stübermania, where I dig into my box of dust-covered interview cassettes from the 1990s and 2000s (and crusty mp3 files from the 2010s) to present bygone conversations with your favourite alterna/indie semi-stars and the occasional classic-rock icon.

This is a newsletter in three parts: The Openers (links to recent writings, playlist updates, and/or other musical musings), The Headliner (your featured interview of the week), and Encores (random yet related links).

This is a free newsletter, but if you really like what you see, please consider a donation via paid subscription, or visit my PWYC tip jar!

THE OPENERS

Over the past quarter-century, I’ve seen Godspeed You! Black Emperor perform in almost every possible venue: small clubs, large concert halls, churches, movie theatres, Pitchfork Festival stages. But last Friday’s headlining appearance at Hamilton’s Supercrawl marked the first time I’d seen them perform in the sort of outdoor street-fair setting where you have an even 1:1 ratio of attentive fans and unassuming food-truck patrons waiting in line for tacos and ice cream. Supercrawl is a free annual weekend-long event and, as such, relies on corporate sponsors to exist—including TD Bank, whose logo hangs above the festival’s mainstage. And if you read my 2008 interview with Godspeed’s Efrim Menuck, you’ll know how he feels about the banking industry. Hours before showtime, Menuck shared this group statement on his Instagram, where they admitted they weren’t aware of the sponsorship ties until it was too late; called out TD’s investments in weapon manufacturers that serve the IDF; and pledged to donate their performance fee to the Palestinian Children’s Relief Fund and Medecins Sans Frontieres. (A similar statement was also projected on the screen as the band took to the stage.) With that business out of the way, Godspeed spent the next 90 minutes showing just how well their roller-coaster orchestro-rock movements work in a public-square environment. (It helps that the band was loud enough to drown out the drunks in the adjacent beer garden.) For a group known for 15-minute songs, abstract film projections, avant-drone soundscraping, and zero stage banter, Godspeed are nonetheless a very accessible band on an emotional and visceral level. And on this night, they forged a common musical language between seasoned post-rock heads, grey-haired dudes in Floyd shirts, hipster parents toting their protective-headgeared kids, and, um, aliens:

Kicking off the bill were stübermania favourites cute, who spent the duration of their set in peak annihilation mode, and proved daytime street-festival mosh pits are the best mosh pits (while eliciting a game-recognizes-game sidestage glance from Menuck):

A few days later, and a few blocks east, I found myself in the polar-opposite situation: In the cozy confines of Into the Abyss watching one-man-band maestro Scott Hardware perform for a mostly seated gathering of 15 or so appreciative souls. I’ve been an admirer of Scott’s since hearing his 2019 single “Bound Together,” and each record he releases—including the upcoming Overpass, out next week—yields more fascinating permutations of classic ‘70s singer/songwriter pop, lush soft-rock orchestration, and indie idiosyncrasies. And even when he’s performing solo to backing tracks, his music retains its sense of mercurial maximalism—where his records present him as a Rundgren-via-Arthur Russell studio auteur, onstage he’s more of a mad scientist in the Panda Bear/Cindy Lee mould, delivering beautifully sung pop tunes via phantasmagoric frequencies.

This week at Pitchfork, I wrote about the triumphant comeback album from The Hidden Cameras, BRONTO, on which Joel Gibb’s Toronto-scene-spawning indie-pop collective is reborn as a one-man Berlin-techno factory.

After premiering last weekend at the Toronto International Film Festival, Lilith Fair: Building a Mystery is now available to stream on CBC Gem in Canada and comes to Hulu the States on Sept. 21. On top of providing a thorough accounting of the festival’s musical and social impact across generations, the film also proves the old adage that whenever there’s a documentary reassessment of a much-maligned, woman-centered ‘90s-era phenomenon, there’s always an old clip of Jay Leno being a dick about it. Earlier this week on Commotion, I produced this discussion of the doc featuring music journos Suzy Exposito, Rosie Long Decter, and Tabassum Siddiqui:

And then today on Commotion, I put together our panel on Kimmelgate with CBC entertainment reporter Jackson Weaver and Rolling Stone internet-culture reporter Alyssa Mercante:

Notes on this week’s additions to the stübermania 2025 jukebox:

Guided by Voices, “(You Can’t Go Back to) Oxford Talawanda”: Robert Pollard’s true superpower is making awkward words that you’d never think of uttering in a sentence together feel like the most natural, mellifluous thing to ever roll off your tongue. And so it goes with the lead earworm from GBV’s upcoming 42nd album (and second of 2025), which basically crosswires “The Official Ironmen Rally Song” with R.E.M.’s “(Don’t Go Back to) Rockville” and wields a hook that lodges itself into your skull so swiftly, you’ll be Googling to see if “Oxford Talawanda” is an actual place before you reach the second chorus. (Spoiler alert: it is.)

Gruff Rhys, “Adar Gwyn”: The former Super Furry Animals frontman’s new album, Dim Probs, is one of his acoustic-oriented, all-Welsh affairs, but non-speakers can easily get on board with this song’s easily graspable “da da da da” refrain and a motorik beat that blurs the line between folky and futurist. (If you missed it, here’s my 2003 conversation with Gruff and SFA bandmate Guto Pryce.)

Odonis Odonis, “Hijacked”: I wrote the bio for the Toronto duo’s forthcoming self-titled sixth album, which sees them dial down the strobe-lit industrial aggression and reimmerse themselves in the ultraviolet goth-adjacent sounds of early ‘80s Cure and New Order.

The Spells, “Lilith”: This song is actually 28 years old, but I only heard it for the first time this week. The Spells were an all-girl New York garage trio—featuring future award-winning author Leni Zumas on drums!—that slipped into the void separating the city’s early-‘90s Jon Spencer-led skronk-rock scene and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ post-Y2K come-up. The group’s aborted 1997 debut album, The Night Has Eyes, is about to be given a proper release for the first time on Oct. 31 (complete with photos taken by a pre-fame Nick Zinner and liner notes by Zachary Lipez), and its lead-off track roils and rumbles like the demonic love child of Bo Diddley and PJ Harvey.

Sword II, “Even If It’s Just a Dream”: I’m always a bit bummed when bands issue the last song on their upcoming record as their lead single, because it feels like you’re spoiling the end of a movie. But I can understand this Atlanta trio’s eagerness to get their sophomore album’s grand finale out into the world as soon as possible, because it fuses Rumours and Loveless into a dream-pop reverie you won’t want to wake up from.

THE HEADLINER:

A conversation with Jarvis Cocker

The date: Aug. 22, 2025

Publication: Toronto Star

Location: I was at my mom’s in Toronto; Jarvis was Zooming in from his home in Peak District in the UK

Album being promoted: More

The context: Pulp played Toronto’s Budweiser Stage this past Tuesday (more on that in the Encores section below), and a few weeks prior to the show, I had the opportunity to interview Jarvis Cocker for the Toronto Star, a mere 27 years after we last spoke. And, as was the case with our previous chat, Jarvis offered up far more quality quotes than can possibly fit into an 800-word profile. So for this week’s stübermania headliner, I’m breaking from the newsletter’s usual archival focus to present you our complete hot-off-the-Zoom conversation:

So how’s country life treating you?

Well, you know, I was born in Sheffield, a very urban place, and I've lived in London, but I've never lived in the countryside, and I do enjoy it. It's different. It was a bit strange at first.

In what way?

Well, you know, I did an art piece about it, actually. Have you heard of the English artist Jeremy Deller? He was asked by the National Trust to do some artworks that were based around places where kind of radical things had happened. The radical thing that happened near where I lived in the countryside is that there was a mass trespass back in the ‘30s. So this was workers from Sheffield and Manchester, they were working in really full-on industrial jobs. And on the weekend, they liked to go to the countryside. But at that time, the countryside in between Sheffield and Manchester was mainly in the hands of landlords who didn't want people on their land. So there were very few places they could go for a walk, and they kept getting arrested and stuff like that. So one weekend they got together workers from Manchester and Sheffield, both synchronized, meeting up at the same time and there were so many of them that they couldn't get arrested, although one or two did. And basically, that got a lot of publicity and therefore, the Peak District became the very first national park in Britain. That happened in the '30s, but it became a national park in the '50s… so yeah, why did I start on that story?

We were talking about country life.

Oh yeah, so Jeremy Deller was asked to do an artwork that kind of went along with that, and he knew that I was living nearby. So I kind of collaborated with him on that. And one of the things we talked about was that both of us didn't feel particularly at home in the countryside, because there's nothing—you don't know what to do, really. There's no signs or anything to tell you what to do. So the art trail that we made kind of bore that in mind. It was supposed to be a kind of non-threatening way of city people finding connection with the countryside.

Were you part of a big exodus from the cities? That happened here during the pandemic…

Yeah, yeah, well that has happened. I mean, I had kind of made the move before then, but I did notice in the village where I am, on weekends, there used to be people who look like ramblers, but now, you get people who look like they’re just going around to shop in town. They wear normal shoes and things like that. It's like they’ve just come in to socialize, really, not to ramble.

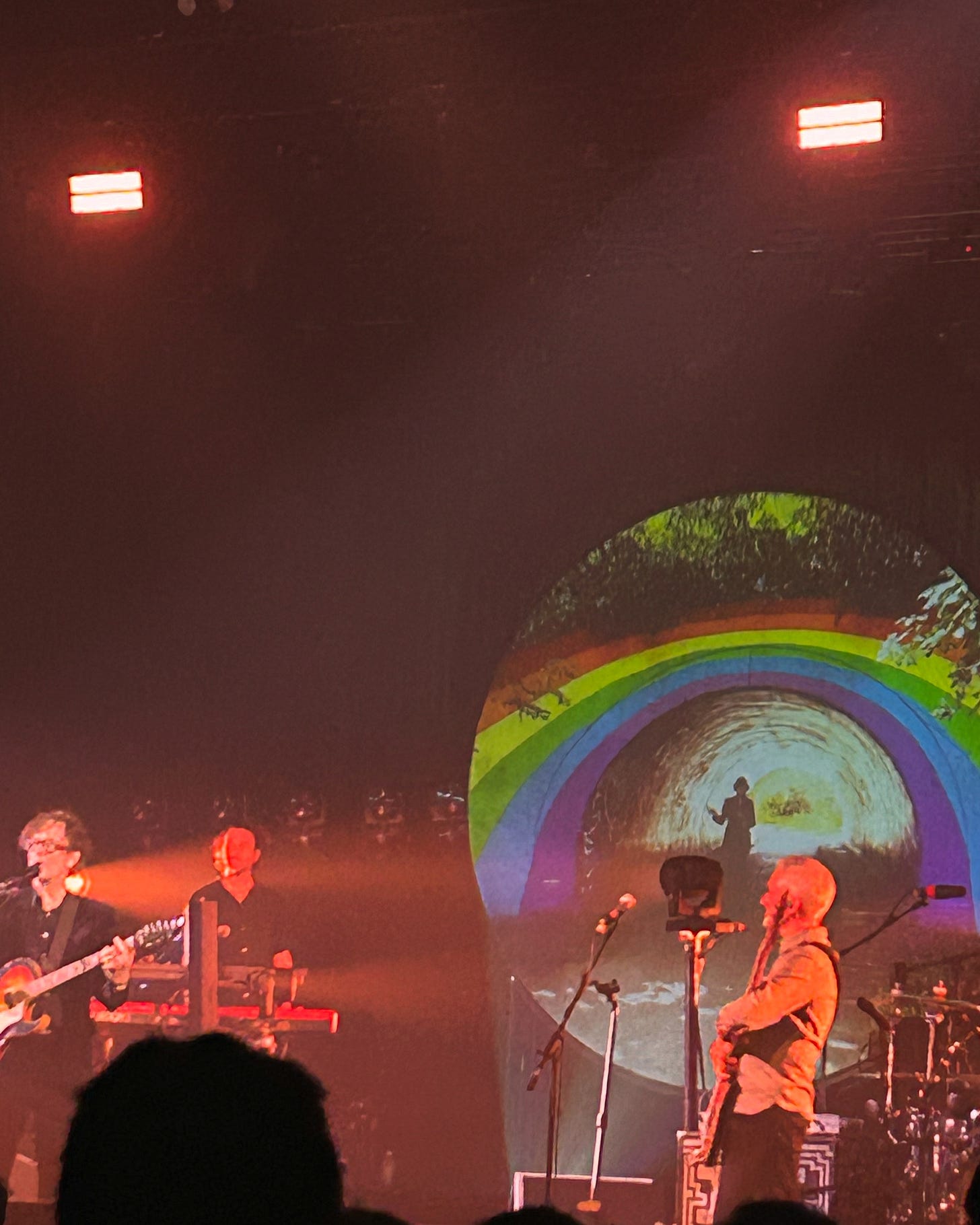

Well, speaking of explorations outside the urban core… when Pulp were in Toronto last September, you put up a photo on the stage screen of you exploring the rainbow tunnel off the Don Valley Parkway, which is not a normal tourist attraction for visitors. So I'm wondering, how you wound up there...

Well, that was interesting. That tunnel features in the greatest hits of Pulp, which nobody really bought in at the time. As part of the artwork, it features a very small reproduction of a Peter Doig painting, which has that rainbow tunnel in it. And I always loved the painting. What I tend to do when I'm on tour, if we've got a bit of time off, I like to do a bit of exploration. I don't really like to go shopping and stuff, so I have a look on Atlas Obscura, and you can just see where you are and it'll show you places nearby. And I saw that tunnel was accessible, so me and Jason Buckle—we were in the band Relaxed Muscle together, but he's also part of Pulp at the moment—we just went for a walk and went and saw it.

Well, keeping with the Canadian theme… when I first listened to More, I was already enjoying the record very much, but then I got to “The Hymn of the North,” and my jaw dropped—I thought that song was just astonishing. And I was very pleased to see our own Chilly Gonzalez had a hand in it. What was his contribution to that track?

So that song was really what got the whole album going, because I'd written that for a play that was on in Manchester in 2019. So it had words and it was arranged, but just for piano. And I sent it to the guy who was doing our string arrangements, Richard Jones, and he started working on an arrangement. And so we ended up playing it. But the thing is, I can't really play the piano, and I certainly can't play the piano and sing very well. So we'd kind of demoed it. I knew we were going to record it for the album and I just thought it would be much better if we got somebody who could actually play the piano to do it, so then I could concentrate on the singing, because the first half of the song hasn't got any drums or anything. So I wanted to get the vocal and the piano at the same time, if possible. So Gonzales spends some time in the UK. He's more in Cologne, but he does come over now and again because his daughter lives here. So I managed to synchronize it, and he came in and he played the piano on that song. I was hoping to try and get him to come to Toronto and play it, but he's doing a tour of his own, so we haven't been able to do it live yet, but I'm hoping we do get to do that at some point.

If I'm not mistaken, was your first ever collaboration for that “Fucking on Heroin” song from the ill-fated Get Him to the Greek?

No, we've done some stuff before then. He had a song called “Francophobia”—I've sang it, and he wrote the lyrics and the music for that. We'd done bits and pieces and then, yeah, we did that stuff for that film. I wanted to do something substantial, but I couldn't think of a project that would work properly. And then, as luck would have it, when Pulp were playing at the Coachella Festival in 2012, I stayed at the Chateau Marmont and I was put in Room 29 of Chateau Marmont, which has a grand piano in it. And I was like, “aha, right—this is it. This piano has seen the whole history of this hotel.” So I rang him very, very excited about that, and said, “I think I've got the project that we could do.” And at first I thought maybe we would actually record it in the room, but that wasn't really practical. So we recorded it in Paris, but that was our major collaboration.

So when Pulp did the reunion tour back in 2011, it felt like there was a finality to the group’s story. It felt like you were doing your victory lap: you did the film and you released the “After You” single and then everything went quiet and it felt like, “well, I guess this is the end.” So at what point did you realize this band still had another chapter left to write?

Yeah, it was unusual because, as you say, that tour that you spoke about in 2011-2012 was kind of conceived as a victory lap… well, not a victory lap, but a kind of goodbye, I suppose. I felt the story of Pulp had kind of just fizzled out. I had moved to Paris and we just kind of lost contact with each other and I just thought it would be nice to kind of tie it up in some way. So that was definitely my idea to do that tour [in 2011-2012], and this last tour [in 2024] wasn't my idea. We were approached by someone who said, "Do you want to do a tour?" and they came up with some dates. And it took me by surprise. I wasn't considering that in the slightest. And I said, “oh, you're going to have to let me think about that for a while, I'm afraid.” So I did think about it, and I spoke to members of the band about it. And I'm glad we did it, because I would have just thought, “that's it—we said goodbye [in 2012], we had a good time. That's it, bye-bye.” But this guy was convinced that if we played, people would come and see us and would enjoy it. He kept saying it. So I just thought, “okay. Let's try it then.” So, it was a completely different concept: It was more somebody else telling me, “you could do this,” and me thinking about it and wondering, “well, okay, would it be worth doing?” And one of the things that convinced me—apart from him just being convinced about it—was this idea of doing something a bit different. When I listened back to Pulp songs, I realized that a lot of them had string arrangements, but we'd never played with a string section. So I thought, “okay, well, let's try that,” that would be interesting to do that. So we did that. And lo and behold, we played and I did discover that people did come and did like it. So he was right.

I read an interview you did recently where you said This Is Hardcore and We Love Life had a conceptual quality to them that slowed down their completion and that you didn't want to burden yourself with any of that this time, and you can think about what the songs all mean after the fact. So now that More has been out for a few months and you've had some distance from it, do you have a clearer picture of what this record is about?

Not a clear picture, no, but I've been doing interviews, so I've had to talk about it. Some insights have come into it, yeah. I mean, I've learned a lot from that approach—the approach of not wanting to think about it too much, and just doing it. Some of the songs talk about that as well—if there is a theme to the record, I guess it's a theme about feelings, about how to trust feelings rather than thoughts. And it's more difficult to do that because thoughts come to you in language and you understand them. Feelings are more kind of nebulous—you can't really express it that well in language. But I kind of realize that thoughts can often just take you off on a not-good tangent, so that's the main theme of the record. It was something that I realized, because the way that I put the lyrics together for this record was a little bit different than in the past because, you know, I'm not a very modern person, but I do have a mobile phone. It took me a long time to have one, I was one of the last people to cave in. My manager eventually just said, “I'm not going to work with you anymore unless you get one,” so I had to get a mobile phone.

How long did you hold out for?

That was just before I went to Paris, which was when my son was born in 2003. And of course, they've got more and more sophisticated. So now rather than getting a notebook out and writing some idea or something that I've heard or whatever, I will get my phone and I will type it in there. So when it came to thinking, “well, okay, maybe we could do a record,” I looked through all the notes I'd written in the previous 10 or 15 years, and tried to discern if there were any patterns or themes that emerged. And that was one thing that I realized: this talking about feelings, feelings versus thoughts, and stuff like that. So, yeah, I went through the phone ,and anything that I thought was interesting, I would start putting them in folders that had a similar kind of thematic thing to them. And then I put those folders onto my iPad—another piece of incredible technology!—and put them into a teleprompter app so that when we were rehearsing, I could press play on the teleprompter and I would have words scrolling up that I would then attempt to sing to whatever music the band was playing.

What we used to do was just me kind of semi-melodically mumbling whilst we were playing. And that would eventually bear some fruit, but it was very, very slow. And one thing that I was aware of was that I put off telling the band that I wanted to make a record for a long time, because I knew that they would be a bit frightened about that, because the previous two Pulp albums had taken a long time and that was mainly my fault for changing lyrics or not being convinced by what I'd sung or whatever. So I wanted to do a lot of the work in advance. So having some words, even though I wasn't quite sure where they were going to go… at least that was starting from a more advanced position.

So it sounds like even when you're not necessarily an active musician or you don't have an album on the horizon, you're still collecting all these thoughts and words and lyric fragments. You're never really turning off the songwriter side of your brain…

Yeah, well, it's more an attitude to life, isn't it? I'm always mystified by how people live and what their goals are. It's not like I expect to find the secret to life, but I am interested in getting insights, so I'm always on the lookout for information, I suppose. And some of that finds its way into songs. A lot of things don't, but yeah, I just find it's an attitude to life, you know. The main attitude that seems to be promoted now is to be a consumer, you know. We're in a kind of post-industrial phase of capitalism, I suppose. And so not so many people are actually working in factories or making the stuff. So the duty of a citizen now seems to be to consume what is produced or is imported from other places. And, you know, we all do it, but I think if you're consuming things, you have to digest them and then maybe make them into something else. If you're just consuming stuff, you'd just become kind of spiritually obese, which is not great.

You've always written songs about relationships and lust and the messy things that happen when people come together. But on this record, songs like “Background Noise” seem to exist on the other side of those moments, when the relationships are at a crossroads. And I'm wondering, as a writer, do you find middle-aged malaise as fertile a ground as young lust?

Well, yeah, I mean, the first person that I played the songs to as we were recording them was my wife. So I obviously had to be confident that she wasn't going to divorce me when she heard the songs. That's another thing I suppose I've found: I'm still writing about the same kind of subject matter that I've always written about, but as you say, it's from a different viewpoint now, because it's more, in some ways, looking back on the choices that I made and the way that I used to look at things and comparing that to how I think now. And also, if you're in long-term relationships, that's a bit of a recurrent theme: how to keep those interesting. Because again, we live in a consumer society, and everything is about built-in obsolescence—you don't expect something to last your whole life. You buy a fridge and you know that you're going to buy another fridge in four years' time or something. And you always trade in your car for another model. But to make a commitment to a person and say, “right, I'm going to spend my life with you,” that goes against that whole consumer concept, really. So it's something that is a difficult thing to deal with. And you have to deal with it in whatever way you can find to deal with it.

So you and I actually sat down for an interview back in 1998 around the time of This is Hardcore…

Have I repeated any of the things I said then?

No, this is all fresh material—thank you! But I was recently revisiting that piece, and we were talking about the song “Help the Aged,” and at the time, you said you were thinking about being an oldish performer—in your mid-30s—operating in a youth-oriented pop market, and how you were pretty much the same age as George Michael, who had already pivoted into adult-contemporary music and you didn't want to fall into that trap. You wanted to make interesting music for older audiences. And it's interesting now to see how artists who came out of the post-punk era, like yourself or Nick Cave, are still making very vital music several decades into your careers versus, say, where The Rolling Stones were at this point in their careers. So I’m wondering if you feel there is more of a place for older artists in the landscape right now.

I hope so! Otherwise, it's bad news for me. The album that I was talking to you about then, This Is Hardcore, on the sleeve notes for that, it says, “It's okay to grow up as long as you don't grow old.” Although there’s a lot of things about that album, I think, I would do differently if I did it now, I still subscribe to that view because you have to develop, you have to grow up, you have to learn things about yourself and about the world. But you don't want to grow old because to grow old is to stop responding to the world, to think that you've seen enough of it, or you know what it's about and not to become curious anymore. I'm touching wood as I'm saying this to you, but I hope that I am still curious about existence in the world.

It seemed like everything Pulp did in the ’90s was viewed through the lens of Britpop and, reading the British music press at the time, it felt like all these bands were just like characters in this ongoing crazy reality show. But how does it feel to exist independent of that now? In a sense, Pulp is sort of its own island now, its own universe. You’re not tethered to this overarching narrative. Is that liberating for you?

Yeah, I mean, we had existed for a long time before that dreaded phrase Britpop was coined and we became part of it in people's eyes. But we never really felt that much part of it. And now that it's a historical fact, rather than an ongoing thing… it was exciting to be considered to be part of the scene, I have to admit, when it first started off, and it seemed like it could be interesting because it was slightly dodgy people getting on a mainstream stage for a short while. And that seemed like maybe that could cause some revolutionary change in the culture. But the culture is strong and it tends to sand off any rough edges, and so that's what happened, really. It got blanded out and you ended up with the Spice Girls and Robbie Williams, you know, which was bad news for everyone.

But as ridiculous as that moment was, it was fuelled by a music press that is now a shell of its former self. So many magazines have shut down. Is there a part of you that misses all that media hysteria, and the fact that there were so many magazines dedicated to covering music, even if some of it was a bit tabloidy?

Yeah, in a way, but there are still some magazines going and they're all right. Writing about music is something I would never want to do, because the people who make music don't know how it works and so talking to someone about it, you'll never really get an insight into it, because the thing about music is it's a bit like a form of magic. It’s taking your life and then dramatizing it and setting it to music, and then it becomes something that communicates with another person, just through hearing the sound of it. And I suppose that's what attracted me to music in the first place: that I couldn't understand why I got these tingly feelings by listening to certain songs when I was younger and wanted to try and be able to do that same piece of magic myself. But that magic—you don't know how you do it. I can tell you the facts about how we went into a studio and how we recorded and who the producer was and all that, and that’s always part of it, but how it became songs that work and hopefully communicate things to people… I haven't got a clue how that works.

ENCORES

I admittedly approached Pulp’s concert at the Budweiser Stage this past Tuesday with some trepidation. After all, the reunion-tour show I saw at History last September (the second of a two-night stand) was a perfect experience, and the upgrade from a 2,500-capacity club to a 16,000-capacity amphitheatre seemed like way too big of a swing. (I mean, I love More, but I don’t think it inspired a three-fold increase in their local audience, even in Britpop-mad Toronto.) Alas, as the gig date approached, there were still wide swaths of blue on the Ticketmaster seat map. But upon arriving at the venue, I saw that ushers were upgrading general-admission lawn-ticket holders to reserved-seat tickets in the 400 section, so by the time Pulp took the stage, all the seated areas were respectably filled out and any misgivings I had about a dampened vibe evaporated. The now-nine-piece band were in top form, and the greatly enhanced stage production gave the show a much more theatrical feel than the History gig. I especially loved the treatment for “This Is Hardcore,” where the red lighting and video backdrop transformed the Bud Stage into Jarvis’ personal den of sin.

And on top of the new More representatives on the setlist, Pulp also played a number of classics they didn’t touch last year, like the mighty “Mis-Shapes”…

…and the humbling “Help the Aged.”

The main set closed, naturally, with their biggest hit, which, after 30 years and 3,000,000 spins, I still never get sick of, because Pulp’s biggest hit also happens to be the greatest song of all time.

This is a free newsletter, but if you really like what you see, please consider a donation via paid subscription, or visit my PWYC tip jar!

Pulp: The greatest British band of the 1990s. No others come close, not even Suede in second place.

Lovely interview, Stuart. Thanks!

Thanks, Stu. I can't get to weeknight shows anymore, but I am glad this one was so good.